Our Research Questions: University of Massachusetts — Boston

- How does the literacy narrative genre honor & engage students’ funds of knowledge to build intercultural transitions when joining new learning contexts?

- How do students in general and multilingual writing classes conceptualize their relationships to English and the additional language(s) in their repertoire?

Methods

The data set comes from two FYW writing sections: one general and one multilingual, both the first of a two-course sequence. Students complete reflective pieces as well as investigations into their own cultural heritage. Three writings were collected: a pre-reflection, a literacy narrative, and post-reflection. Additionally, students completed structured cross-cultural interaction with classmates.

We have further implemented a standardised measure, the Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale (Miville et al 1999), to triangulate findings related to understanding similarity and difference. In the pre-reflection, students examined their language repertoire and their relationship to English as well as the connections between literacies, motion, and mobility.

The autoethnographic cultural literacy narrative invited students to investigate the sources of their own various literacies, and what contexts gave rise to these literacies. Finally, the post-reflection promoted cultural interaction through exploration of differences within similarity and similarities within difference. These explorations cultivated self-understanding and other-understanding, both of which are key to intercultural competence development and thriving in HE settings (American Association of Colleges & Universities, 2012).

To analyse this data set, we have developed a unique analytical heuristic that expands Tara Yosso’s (2005) work on types of capital that make up community cultural wealth. As we are in a learning context, we engage these types of capital as “funds of knowledge.” We have identified a set of sub-codes that signal how students engage aspirational, familial, navigational, and linguistic funds of knowledge. We identify a further fund of knowledge: intercultural — knowledge, attitudes, and skills that support effective interaction in a variety of cultural contexts — that students operationalise as a part of transitioning to HE settings, and as a part of movement across borders more generally.

We analyse student writing via a collaboratively-created coding scheme as well as two qualitative synthesis questions:

- How are students using these funds of knowledge?

- How do students conceptualize their relationship with language?

Our Research Questions: Purdue University

- How can first-year writing curricula effectively develop all students’ intercultural competence and better promote social and academic adjustment for international and diverse domestic students?

- How can we assess the effects of the curriculum on improving students’ intercultural competence?

Thus, in our pedagogical, empirical research project, we seek not only to develop students’ intercultural competence, but also to develop methods of assessment that work for both intercultural competence and writing skills. This dual-purpose assessment is reflected in our coding scheme. Additionally, we seek to measure skill levels as well as trace the paths by which students develop these skills.

Methods

We employ a mixed-methods approach for our project. The data collected comes from demographic surveys, student reflective writing, semi-structured follow-up interviews, and teacher-researcher experiences as well as from a standardized measure of intercultural competence– the Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale Short Form (MGUDS-S). Our analytical methods integrate qualitative and quantitative analysis to offer a nuanced, thorough understanding of participants’ writing skills and intercultural competence development during the introductory composition course.

We have developed a rigorous grounded-theory coding scheme for student reflective writing. This coding scheme enables detailed analysis of cultural themes and meta-cognition in student writing. While our coding scheme is primarily qualitative, we are also able to trace frequencies of codes across documents to have a quantitative view of course outcomes and cultural competencies.

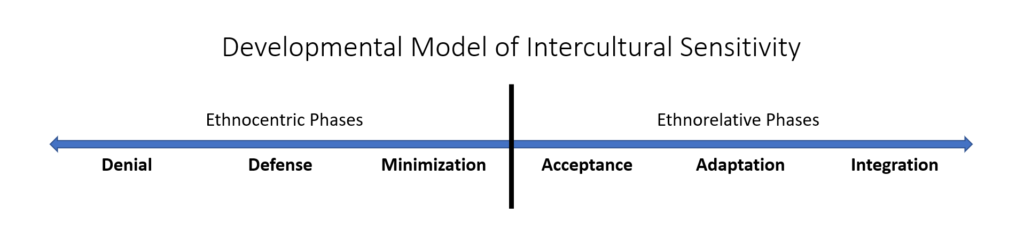

After this first level of coding, we map students’ documents onto the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) to understand larger-scale changes across the entire semester. Our grounded theory coding offers insight into the different ways that students move through the DMIS phases.

To map the students’ writings on the DMIS scale, we each assigned the piece of writing a particular phase or phases, and justified that decision. We then met to resolve any differences in evaluation by discussing the evidence together. We share an in-depth look at how we evaluated and came to an agreement on a student’s DMIS profile here.

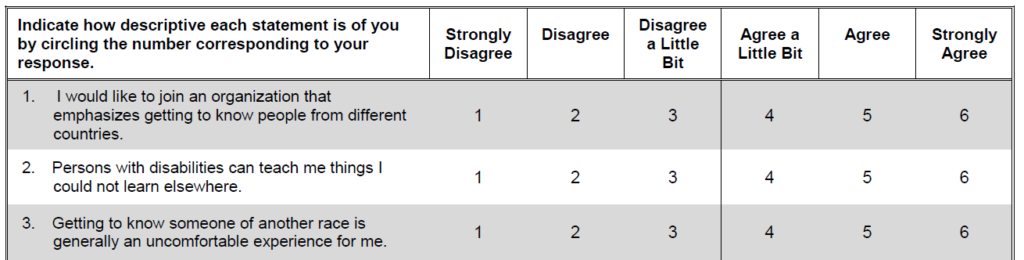

In our second and third rounds of curriculum implementation (Fall 2017 and Spring 2018), we collected pre- and post-course measures of intercultural competence via the MGUDS-S. The MGUDS-S is a 3-factor measure that uses a 6-point Likert scale. The three subscales measure participants’ level of curiosity about other cultures, empathy, which is the relative appreciation of difference in other cultures, and openness i.e. comfort with difference. These results are analyzed in the aggregate to trace the development of the classes as a whole.

See below for a sample of items from the MGUDS-S.

Transparency about our data collection and analytical procedures is important to us. Our coding scheme can be found here:

If you are interested in learning more about our approach to data coding, please contact us at info@writeic.org.

References

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (pp. 21–71). Yarmouth, Me: Intercultural Press.

Bennett, Milton J. (1986). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(86)90005-2

Fuertes, J. N., Miville, M. L., Mohr, J. J., Sedlacek, W. E., & Gretchen, D. (2000). Factor Structure and Short Form of the Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 33(3), 157.

Yosso, T. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69-91.